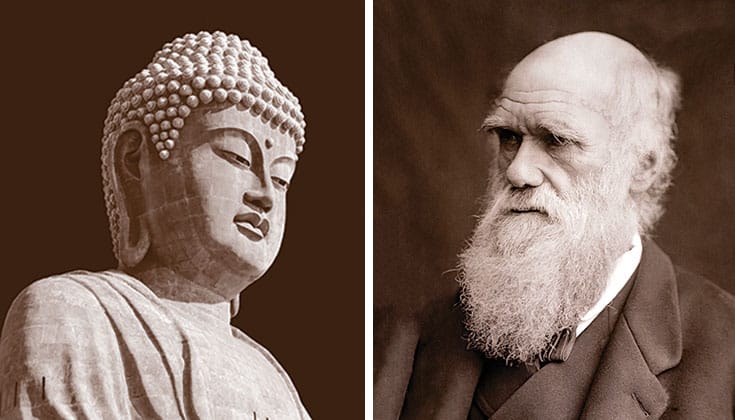

Buddha photo: © Liewluck / Dreamstime. Darwin photo: Paul D Stewart / Science Photo Library.

Darwin and the Buddha agree on the problem, says evolutionary psychologist Robert Wright. The Buddha solved it. From the November 2017 Lion’s Roar magazine.

Melvin McLeod: Your new book, Why Buddhism Is True: The Science and Philosophy of Meditation and Enlightenment, is getting more mainstream attention than any other Buddhist-oriented book I can think of. Were you consciously trying to reach people who would normally turn their nose up at a book about Buddhism?

Robert Wright: I wanted to show people that the Buddhist diagnosis makes sense from a modern point of view. It is compatible in many ways with modern psychology and evolutionary psychology. It makes perfect sense in light of the modern understanding of the evolutionary process that created us.

There are many people who are resistant to Buddhism — perhaps because they think it’s unscientific. I hope my trying to place the practice, philosophy, and psychology of Buddhism in the context of modern science will help make it more credible in the eyes of people who are currently suspicious of it.

Tell us about your background as a Buddhist practitioner.

Since college I tried to meditate every once in a while, but I never had what I considered success. Finally, in 2003, I went to a one-week silent meditation retreat at the Insight Meditation Society in Massachusetts. That kind of flipped the switch. By the end of the week I felt much more appreciative of beauty, much less judgemental, and much calmer. I did another retreat in 2009, and since then I have been pretty consistent in my mindfulness practice.

So what have you discovered that Buddhism is right about?

In 1994, I wrote a book about evolutionary psychology called The Moral Animal. That project convinced me that natural selection did not design us to be lastingly happy. It did not design us to always see the world clearly. In fact, evolutionary theory predicts that if certain illusions help genes get into the next generation, then those illusions — about the nature of the self, and about other people and other things — will be favored by natural selection.

In my study of evolutionary psychology, I came to appreciate three things about the human condition: that, by its nature, happiness tends to evaporate; that in many ways we don’t see ourselves or the world clearly; and that, by nature, we are not always morally good, even though we’re good at deceiving ourselves into thinking we’re moral people.

I see Buddhist practice as, in some sense, a rebellion against natural selection.

Buddhism claims that these three things are connected. It says the reason we suffer, the reason we’re not enduringly satisfied, is that we don’t see the world clearly. That’s also the reason we sometimes fall short of moral goodness and treat other human beings badly. I was naturally interested in this proposition, given my background in evolutionary psychology.What I’m arguing in this book is that looking at Buddhism through the lenses of modern psychology — and evolutionary psychology specifically — tends to validate Buddhism’s claims. When we look at the subtle ways natural selection has built illusion into us, that tracks the two most fundamental Buddhist claims about our illusions, namely that we fail to see the truths of not-self and emptiness.