—Dawa Tarchin Phillips, “What to Do When You Don’t Know What’s Next”

CLICK HERE TO READ THE FULL ARTICLE

A personal blog by a graying (mostly Anglo with light African-American roots) gay left leaning liberal progressive married college-educated Buddhist Baha'i BBC/NPR-listening Professor Emeritus now following the Dharma in Minas Gerais, Brasil.

“A riqueza não monetária é muito interessante, porque ela pode quantificar o que perdemos na nossa vida quando nos ligamos à economia monetária, quando trocamos os parâmetros de qualidade de vida, sustentabilidade e sanidade do ambiente. Trocamos isso por uma aparente vantagem da riqueza monetária, mas na verdade estamos empobrecendo, ficando mais vulneráveis e mais infelizes.

Se olharmos, por exemplo, o que acontece quando ficamos presos a esse percurso da sociedade ligado à economia monetária, vamos entender que há um sofrimento muito amplo, que surge de algum modo ligado a coisas econômicas, mas que vai impactando também outras formas de funcionamento da própria sociedade. Quando a pessoa mergulha na visão do paradigma econômico monetário, é quase impossível entender a visão ecológica. Surge também uma sensação de que não há limites para esse crescimento econômico.

Quando começamos a estabelecer um tipo de sociedade, não conseguimos incorporar a visão de equilíbrio entre as múltiplas espécies e de limitação da atividade humana. Não perseguimos riqueza, nós passamos a perseguir números, como se fosse um jogo, e então a visão ecológica perde o sentido. Eu preciso atravessar a vida dos outros seres, preciso avançar sobre a liberdade dos outros seres para ampliar esses números.”

— Lama Padma Samten apresentando uma economia desde a visão budista na seção Palavras do Lama, na Revista Bodisatva 33.

On this day in 1855, WALT WHITMAN published the first edition of Leaves of Grass. The first edition consisted of twelve poems, and was published anonymously; Whitman set much of the type himself, and paid for its printing. Over his lifetime, he published eight more editions, adding poems each time; there were 122 new poems in the third edition alone (1860-61), and the final "death-bed edition," published in 1891, contained almost 400. The first edition received several glowing — and anonymous — reviews in New York newspapers. Most of them were written by Whitman himself.

The praise was unstinting: "An American bard at last!" One legitimate mention by popular columnist Fanny Fern called the collection daring and fresh. Emerson felt it was "the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom America has yet contributed." This wasn't a universal opinion, however; many called it filth, and poet John Greenleaf Whittier threw his copy into the fire.

When you look at the world, you will see that there are many different levels of spiritual evolution. They are merely stages of development. Be careful not to impose values of 'better' or 'worse'. It is no better to be an adolescent than to be a child. It is no better to be an old person than middle age. These are just different stages of development.

- Ram Dass -

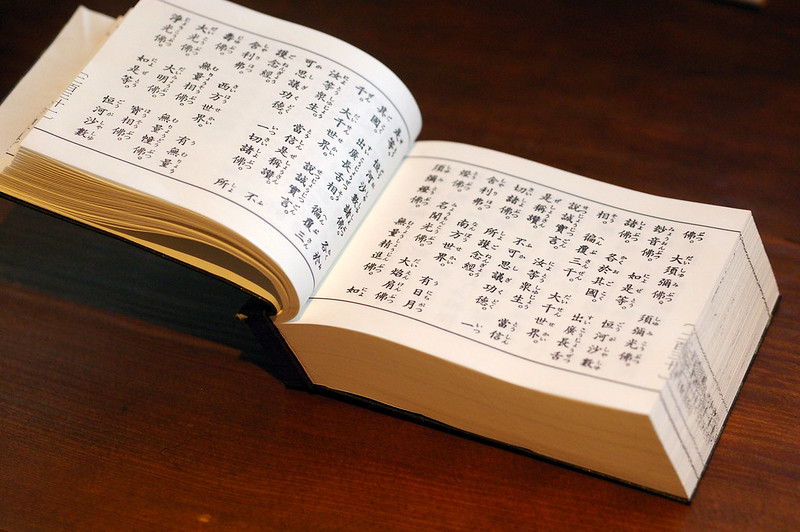

Six steps for easing into and learning to love these sacred texts, and recommended reading for getting started

After starting my apprenticeship as a translator of Buddhist texts more than ten years ago, I found that as I took the sutras to heart, they began to work fantastic changes in my life.

But it didn’t happen overnight. Many of us want to read the sutras. If you’re like me, you’ve gone to the bookstore and brought home a Buddhist book or four—maybe more. If we’re being honest, though, the sutras live on the bookshelf, not the nightstand. Or they linger around the house like visitors at a party to whom we’ve not been properly introduced. That’s because, for many of us, though they brim with helpful wisdom, they’re unlike the other books we’ve read. We open them and find ourselves at a loss, so we don’t read them, not very much.

This reminds me of a time when my teacher and I were walking through a park, and I was scrutinizing the ground for pieces of litter to discard. After the walk, my teacher asked me, “What did you see?” While I’d learned a great deal about the surface of the asphalt walkway, I had no sense of the hills and groves we’d traversed. I knew a few details, but not the terrain. Over the years, we returned to this park many times, and eventually I learned its paths, its edges, and where the tallest trees stood. And I came to know deeper, overgrown places where the path was harder to discern.

Likewise, learning to read—and to love—the sutras happens only as we return to them over and over again.

The sutras, however, are much vaster and more intricate than even the grandest park. They spill out past the borders of the ancient civilizations that gave rise to them. They are buddha-worlds unto themselves, visions of reality extending beyond the reaches of imagination. They are realms of boundless magic, at the center of which we find ourselves standing, from the turning of the very first page.

When first encountering the sutras, bewilderment is a natural response. Even if we later become close friends, at first we don’t even know where to start with them.

To help you begin to make friends with the sutras, I want to share with you what I’ve learned by returning to them throughout the years.

1. Find the time (don’t “make” it). The standard advice here is to tell you to put down your smartphone or cancel Netflix. This may not be very helpful—unless perhaps you were hoping to stare into the gaping maw of your underlying loneliness today? You were not? Great, then let’s keep those habits where they are for one more day. Those precious sentinels are there for a reason, leave them be!

When I say find the time, I’m not talking about ridding yourself of other activities. I’m talking about identifying available time in your day just as it is. A five minute window, or ten maybe. Twenty would be heroic. Half an hour would be a real coup.

Here’s where I found some time in my own day: I noticed that I was spending ten minutes every day standing slack-jawed in the kitchen, vacantly regarding a cooking pot of oatmeal. I wasn’t doing anything particular during that time, for well or ill. My habit was just to stand there and watch the oatmeal do its thing, and not in a “mindfulness practice” way.

Turns out the oatmeal didn’t need my attention, only a timer. So I resolved to use that time constructively: ten pristine, unclaimed minutes. That small a span of time, even half that—that’s your sutra reading practice, right there. It can literally be “five minutes a day that will change your life.”

2. Don’t read the sutras. (I’m kidding!!) We’ve already settled on reading the sutras. But what I mean is, especially if you’re new to Buddhist literature, you might be happier beginning with a contemporary paraphrase or adaptation. In this way you can get to know, in a more familiar literary form, the main personalities, events, and teachings that populate the sutras themselves.

For instance, Thich Nhat Hanh’s gentle, glorious masterpiece Old Path White Clouds tells the Buddha’s life story in language as beautiful as it is accessible. Many of the Buddha’s significant deeds are recounted here—his awakening, his central teachings, his eventual passing into final nirvana, and more in between.

I read it early in my studies, and frankly wept at more than one point in the book. But after making the Buddha’s acquaintance in such a living, moving way, I found that I resonated deeply with him afterward, anytime he appeared in the sutras. Whether they are in a biographical novel like this, or another form such as Osamu Tezuka’s manga series Buddha, paraphrases and adaptations can be the shortest route to a lifelong love of the sutras.

3. Read the sutras… slowly. These days we’re used to consuming content rapidly, no matter what we’re looking at. But please, do not plow through the sutras like you’re doomscrolling the news.

To read slowly means, for one, to read in smaller chunks than one otherwise might. Especially when it comes to sacred texts, it can be better to spend a year or more burrowing slowly into a single one, really snuggling into it, than it is to run through a book a week and retain nothing but a sense of rush.

In fact, the masters tell us that great realizations can come on the basis of very short texts, rather than an entire book—sometimes just one stanza, or a single line. Understand this, and grant yourself the joy of appreciating some tiny sliver of your sutra.

Even the shortest teaching—maybe just a phrase—once it’s written on your heart, will spring up to offer help when you need it.

4. Be aware of your expectations, and be ready to recalibrate.

The sense of boredom we sometimes feel has a lot to do with unmet expectations. When it comes to storytelling, we may be used to a deeply psychological style of narrative, with particular conventions for explaining why characters act the way they do. There are modern conventions also around suspense, plotting, character development, tension, and resolution.

These conventions are what make a good twist possible—and what blockbuster these days doesn’t involve a twist or two?

The sutras may not share in these conventions. Many of the stories they tell were passed down in oral tradition before ever being committed to the page. For this reason among others, they can be quite unlike what we are accustomed to.

The sutras are nearly always more repetitive than we might like at first. And what’s up with these occasional stretches of verse? Why do people in certain stories suddenly burst into song? Did I just sit down to watch the television musical series Glee? Have I accidentally picked up a copy of J.R.R. Tolkien’s turgid, inexplicably song-filled history of Middle Earth, The Silmarillion?

If we’re not ready for these differences, they can become real stumbling blocks to approaching the sutras. There are a lot of ways to accommodate them and make your reading practice more enjoyable. But the simplest way to make it work might just be this:

5. Take time to identify with each person in the story, however large or small their role.

The (relative) lack of psychological detail in the sutras when compared to, say, Madame Bovary, actually leaves space for wonderment. We can ask ourselves, “Why would this person do this? What does that situation feel like? Who do I identify the most readily with, and who the least?”

What about those characters at the margins of certain stories—enslaved persons, eunuchs, spellcasters, denizens of hell? What do they make of the events taking place? How might they have felt about what they saw? What do they need, and how will they get it?

It is also a powerful practice to extend this identification to the Buddha and his disciples. What does it feel like when the Buddha “looks out in wisdom”? What might we see, if we understood karma as he does? What would it be like to possess the Buddha’s great compassion? What would we do then?

In asking these questions, we can start to understand the assumptions we bring to the sutras, and what the people in them are or could be. This provides a special opportunity to grow.

My final advice is:

6. Stop While You’re Still Having Fun. Learn to pay attention to your mental state, recognize fatigue before it sets in, and go easy on yourself.

Unless you have a certain amount you need to cover for some reason, when it comes to a regular practice of reading the sutras, less can be more. “Stop while you’re still having fun” is a quintessential meditation instruction, because stopping while you’re still enjoying the task means that you will have a positive memory of the time you spent, and be eager to return. The same goes for reading the sutras.

If you can get it right, and bring your reading practice to a close in a happy manner two or three days in a row, it will start to become a habit. That habit will bring energetic benefits over a few days, a week, or a month.

After that, pay attention to what happens when you don’t read for a day or two. If then you have what seems like an “unrelated” bad day, or a stretch of them—make a mental note. Remarking to yourself about the difference a few skipped days can make will instill a heartfelt and happy desire to read the sutras.

In time you’ll come to know an uncommon joy—the gift that comes from spending time each day with these precious beings in your heart.

A few suggestions to jumpstart your sutra reading practice:

1. Metta Sutta: Just two stanzas long, this sutta (as they are called in Pali) is a classic of the genre. It is profound, beautiful, and stirring. Recommended for practitioners of all levels looking for a deep well of wisdom they can draw from swiftly, that never runs dry.

2. Faith Mind Poem: Linked here in PDF form suitable for printing, these beautifully translated verses from the Zen tradition are a perfect foundation for infinite reflection. Faith Mind Poem is a wonderful read in any amount—in its entirety or any smaller part—like a diamond whose every refraction is of surpassing beauty.

3. Old Path White Clouds. A fantastic choice for novel gobblers. When Thich Nhat Hanh set out to paraphrase a number of foundational Chinese Mahayana sutras in novel form, he did so in a thoughtful way deliberately aimed at contemporary readers. The result is approachable, enjoyable, and breathtaking.

4. Buddha. Osamu Tezuka’s multi-volume series of graphic novels openly allows itself to stray somewhat from the Buddha’s story as told in the sutras. But it does so in just the ways that make for a gripping, exciting read. This choice is especially recommended to those who are visually-inclined, who love the graphic novel format, or are looking for something different from the usual Buddhist literary fare.

5. The Hundred Deeds. This sutra, just translated into English for the first time (full disclosure: in part by our writer!), and published by 84000.co, has been having a moment lately. It abounds with tales of ordinary people whose stories provide the fodder for important teachings from the Buddha on karmic cause and effect. In turns hilarious and heartbreaking, this sutra is now also available in a new illustrated edition.

♦

For more, check out Dhamma Wheel, a daily email course designed to deepen your understanding of Buddhist wisdom and gradually integrate it into your meditation practice and your life. Sign up and you’ll receive one email per day containing a brief study text from the Pali canon, a commentary, and a practical contemplation for that day.

Make the jump here to read the original and subscribe to Tricycle

|