A personal blog by a graying (mostly Anglo with light African-American roots) gay left leaning liberal progressive married college-educated Buddhist Baha'i BBC/NPR-listening Professor Emeritus now following the Dharma in Minas Gerais, Brasil.

Thursday, September 26, 2019

Via Daily Dharma: Finding Joy in Simplicity

It’s

in precisely those moments when we experience how crowded our minds are

that we have the chance of letting go and experiencing just how light

we can be. What a joy to simply bow and light a stick of incense.

—Noelle Oxenhandler, “Twirling a Flower”

CLICK HERE TO READ THE FULL ARTICLE

—Noelle Oxenhandler, “Twirling a Flower”

CLICK HERE TO READ THE FULL ARTICLE

Wednesday, September 25, 2019

Via Lions Roar: I Vow Not to Burn Out - Mushim Ikeda says it’s not enough to help others. You have to take care of yourself too.

At the end of January, one of my close spiritual friends died. A queer Black man, a Sufi imam “scholartivist” (scholar–artist–activist) and professor of ministry students, Baba Ibrahim Farajajé died of a massive heart attack. He was sixty-three, and I’m guessing he had been carrying too much. It was only six months earlier that Baba and I had sat together on a stage in downtown Oakland, California, under a large hand-painted banner that read #BlackLivesMatter. A brilliant, transgressive bodhisattva, Baba had been targeted for multiple forms of oppression throughout his life and had not been silent about it. When he died, I was sad and angry. I took to staying up all night, chanting and meditating; during my daytime work, I was exhausted.

How many of us who have taken the bodhisattva vow are on a similar path toward burnout? Is it possible for us, as disciples of the Buddha, to engage with systemic change, grow and deepen our spiritual practice, and, if we’re laypeople, also care for our families? How can we do all of this without collapsing? In my world, there always seems to be way too much to do, along with too much suffering and societal corruption and not enough spaces of deep rest and regeneration.

When I get desperate, which is pretty often, I ask myself how to not be overwhelmed by despair or cynicism. For my own sake, for my family, and for my sangha, I need to vow to not burn out. And I ask others to vow similarly so they’ll be around when I need them for support. In fact, I’ve formulated a “Great Vow for Mindful Activists”:

Aware of suffering and injustice, I, _________, am working to create a more just, peaceful, and sustainable world. I promise, for the benefit of all, to practice self-care, mindfulness, healing, and joy. I vow to not burn out.

The cosmic bodhisattvas like Sadaparibhuta and Avalokitesvara and the rest of the gang don’t burn out. Maybe they have big muscles from continuously rowing suffering beings to the farther shore. They are willing to take abuse while demonstrating unfailing respect and love toward sentient beings. When something bad happens, they immediately absorb the blame. They vow to return, lifetime after lifetime, until the great work is fully accomplished, and until that probably distant time they remain upbeat, serene, and self-sacrificing.

I love this section from the poem “Bodhisattva Vows” by Albert Saijo:

… YOU’RE SPENDING ALL

YOUR TIME & ENERGY GETTING OTHER PEOPLE

OFF THE SINKING SHIP INTO LIFEBOATS BOUND

GAILY FOR NIRVANA WHILE THERE YOU ARE

SINKING – & OF COURSE YOU HAD TO GO & GIVE

YOUR LIFEJACKET AWAY – SO NOW LET US BE

CHEERFUL AS WE SINK – OUR SPIRIT EVER

BUOYANT AS WE SINK

This poem never fails to give me a refreshing laugh; the archetype of bodhisattva activity it presents resonates with my early Buddhist training. But I have changed. In the social justice activist circles I travel in, giving your lifejacket away and going down with the sinking ship is now understood as a well-intentioned but mistaken old-school gesture—right now, the sinking ship is our entire planet, and there are no lifeboats. As the people with disabilities in my sangha have said, in order to practice universal access there needs to be a radical shift toward an embodied practice of “All of us or none of us.” In other words, no one can be left behind on the sinking ship, not even those who want to self-martyr. Why? Because self-martyrdom is bad role modeling. Burnout and self-sacrifice, the paradigm of the lone hero who takes nothing for herself and gives everything to others, injure all of us who are trying to bring the dharma into everyday lay life through communities of transformative well-being, where the exchange of self for other is re-envisioned as the care of self in service to the community. The longer we live, the healthier we are; the happier we feel, the more we can gain the experience and wisdom needed to contribute toward a collective reimagining of relationships, education, work, and play.

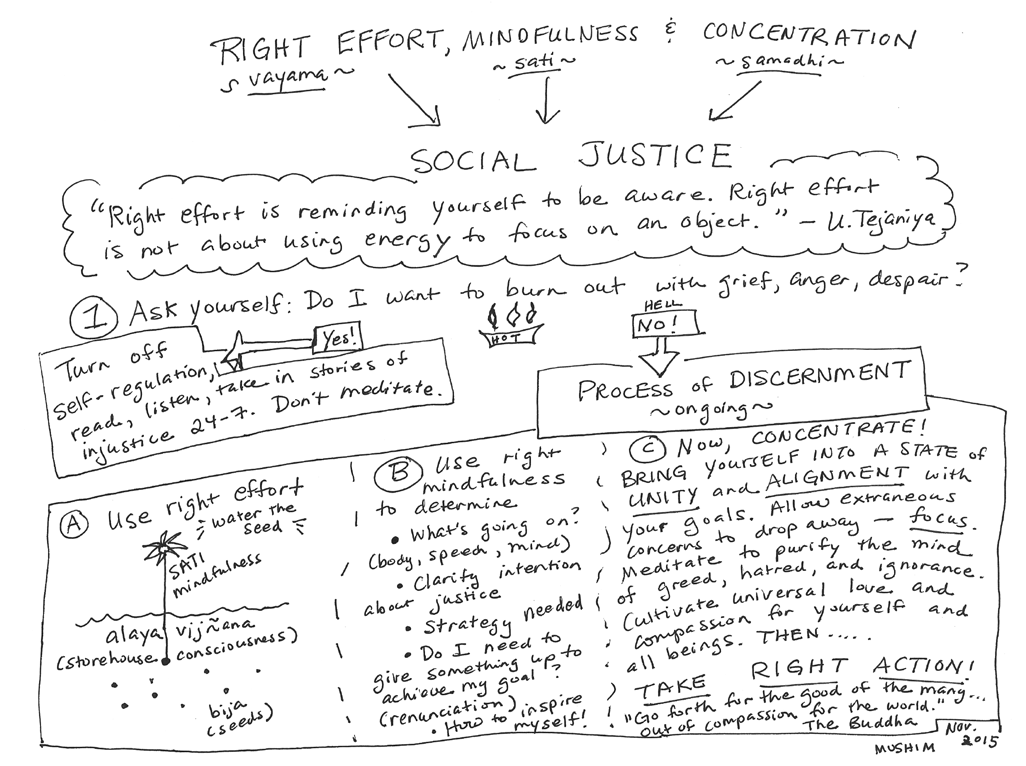

Infographic by Mushim Patricia Ikeda from a class titled

“Right Mindfulness, Concentration, Effort, and Social Justice:

“Right Mindfulness, Concentration, Effort, and Social Justice:

Here in Oakland, I don’t think it’s melodramatic or inaccurate to say that we now live in the midst of multiple ongoing crises. Thich Nhat Hanh has said that the future Buddha, Maitreya, may be a community, not an individual. Perhaps your community, like mine, is in need of inventive ways to carve out spaces for what some are now calling “radical rest.”

I advocate for more forgiving and spacious schedules of spiritual practice that value being well-rested and that move toward honoring the body–mind’s need for enough sleep and downtime. Social justice activist Angela Davis, in an interview in YES! Magazine, says:

I think our notions of what counts as radical have changed over time. Self-care and healing and attention to the body and the spiritual dimension—all of this is now a part of radical social justice struggles. That wasn’t the case before. And I think that now we’re thinking deeply about the connection between interior life and what happens in the social world. Even those who are fighting against state violence often incorporate impulses that are based on state violence in their relations with other people.

We need a path of radical transformation, and there’s no question in my mind that the bodhisattva path is it.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and his fellow organizers sometimes planned protests to occur at around eleven in the morning, because then the people who were arrested would get lunch in jail and wouldn’t have to wait many hours to eat. For those of you who may feel that social-change work isn’t your thing, or that it’s too big to take on, it may help you, as it helped me, to know that it often comes down to these little details. Every movement is made of real people, and every action is broken down into separate tasks. This is work we need to do and can do together.How can you make your life sustainable—physically, emotionally, financially, intellectually, spiritually? Are you helping create communities rooted in values of sustainability, including environmental and cultural sustainability? Do you feel that you have enough time and space to take in thoughts and images and experiences of things that are joyful and nourishing? What are your resources when you feel isolated or powerless?

Samsara is burning down all of our houses. We need a path of radical transformation, and there’s no question in my mind that the bodhisattva path is it. Speaking as a mother and a woman of color, I think we’re all going to need to be braver than some of us have been prepared to be. But brave in a sustainable way—remaining with our children, our families, and our communities. We need to build this new “woke” way of living together—how it functions, handles conflict, makes decisions, eats and loves, grieves and plays. And we can’t do that by burning out.

make the jump here to read the original, join Lion's Roar and read much more!

Via White Crane Institute / Gay Wisdom

1949 -

PEDRO ALMODOVAR, Spanish filmmaker, was born; Almodóvar is the most successful and internationally known Spanish filmmaker of his generation. His films, marked by complex narratives, and quirky stylings, employ the codes of melodrama and use elements of pop culture, popular songs, irreverent humor, strong colors and glossy décor. He never judges his character's actions, whatever they do, but he presents them as they are in all their complexity. Desire, passion, family and identity are the director's favorite themes. Almodóvar is openly – dare we say brilliantly? -- Gay and he has incorporated elements of underground and gay culture into mainstream forms with wide crossover appeal, redefining perceptions of Spanish cinema and Spain in the process. At one time, it is believed, he owned the film rights to Tom Spanbauer’s mystical book, The Man Who Fell In Love With the Moon (though we now believe Gus Van Sant has these rights.)

Around 1974, Almodóvar began making his first short films on a Super-8 camera. By the end of the 1970s they were shown in Madrid’s night circuit and in Barcelona These shorts had overtly sexual narratives and no soundtrack: Dos putas, o, Historia de amor que termina en boda (1974) (Two Whores, or, A Love Story that Ends in Marriage); La caída de Sodoma (1975) (The Fall of Sodom); Homenaje (1976) (Homage); La estrella (1977) (The Star) 1977 Sexo Va: Sexo viene (Sex Comes and Goes) (Super-8); Complementos (

“I showed them in bars, at parties… I could not add a soundtrack because it was very difficult. The magnetic strip was very poor, very thin. I remember that I became very famous in Madrid because, as the films had no sound, I took a cassette with music while I personally did the voices of all the characters, songs and dialogues.” After four years of working with shorts in Super-8 format, in 1978 Almodóvar made his first Super-8, full-length film: Folle, folle, fólleme, Tim (1978) (Fuck Me, Fuck Me, Fuck Me, Tim), a magazine style melodrama. In addition, he made his first 16 mm short, Salome. This was his first contact with the professional world of cinema. The film's stars, Carmen Maura and Felix Rotaeta, encouraged him to make his first feature film in 16mm and helped him raise the money to finance what would be Pepi Luc: Bom y otras cgicas del monton.

Almodóvar's subsequent films deepened his exploration of sexual desire and the sometimes brutal laws governing it. Matador is a dark, complex story that centers on the relationship between a former bullfighter and a murderous female lawyer, both of whom can only experience sexual fulfillment in conjunction with killing. The film offered up desire as a bridge between sexual attraction and death.

Almodóvar solidified his creative independence when he started the production company El Deseo, together with his brother Agustín, who has also had several cameo roles in his films. From 1986 on, Pedro Almodóvar has produced his own films.

The first movie that came out from El Deseo was the aptly named Law of Desire (La Ley del Deseo). The film has an operatically tragic plot line and is one of Almodóvar’s richest and most disturbing movies. The narrative follows three main characters: a Gay film director who embarks on a new project; his sister, an actress who used to be his brother (played by Carmen Maura), and a repressed murderously obsessive stalker (played by Antonio Banderas).

The film presents a gay love triangle and drew away from most representations of Gay men in films. These characters are neither coming out nor confront sexual guilt or homophobia; they are already liberated, like the homosexuals in Fassbinder’s films. Almodóvar said about Law of Desire: "It's the key film in my life and career. It deals with my vision of desire, something that's both very hard and very human. By this I mean the absolute necessity of being desired and the fact that in the interplay of desires it's rare that two desires meet and correspond."

Almodóvar's films rely heavily on the capacity of his actors to pull through difficult roles into a complex narrative. In Law of Desire Carmen Maura plays the role of Tina, a woman who used to be a man. Almodóvar explains: "Carmen is required to imitate a woman, to savor the imitation, to be conscious of the kitsch part that there is in the imitation, completely renouncing parody, but not humor".

Elements from Law of Desire grew into the basis for two later films: Carmen Maura appears in a stage production of Cocteau’s The Human Voice, which inspired Almodóvar’s next film, Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown; and Tina's confrontation scene with an abusive priest formed a partial genesis for Bad Education.

Via Tricycle: Sutta Study: The Hawk

This article is part of Trike Daily’s Sutta Study series, led by Insight meditation teacher Peter Doobinin. The suttas are found in the Pali Canon, which contains some of the earliest Buddhist teachings. Rather than philosophical tracts, the suttas are a map for dharma practice. In this series, we’ll focus on the practical application of the teachings in our day-to-day lives.

In The Hawk (Sakunagghi Sutta), the Buddha offers a compelling parable to illustrate the importance of practicing right mindfulness. The Buddha didn’t simply teach mindfulness. He taught right mindfulness. In practicing right mindfulness, the dharma student makes an effort to keep her mind on specific objects: the four foundations of mindfulness (or the four establishings of mindfulness, according to Thanissaro Bhikkhu’s translation). If we’re able to do so, we’ll move toward a true happiness in our lives. But if we don’t keep the mind in these places, the Buddha teaches, we’ll be bound to suffer.

The Buddha makes this point by telling the story of a quail who lives in a field with “clumps of dirt all turned up.” As long as she remains in this field, her “proper range,” she’s safe from predators, including the hawk. One day, however, the quail wanders outside the field, and, sure enough, the hawk swoops down and captures her. The quail laments her “bad luck,” remarking that if she’d stayed in the field of turned up dirt, the hawk “would have been no match for me in battle.” The hawk disagrees, and, to make his point, he deposits the quail back in the field. The hawk circles and swoops down. The quail, in turn, conceals herself behind a large clump of earth. And, sure enough, the hawk smashes into the dirt and dies.

The moral of the story is that we shouldn’t wander into what isn’t our “proper range.” The Buddha tells us: “In one who wanders into what is not his proper range and is the territory of others, Mara gains an opening, Mara gains a foothold.” Mara, in Buddhist lore, is the personification of unskillful qualities: desire, aversion, and delusion.

The Buddha goes on to say that the five strings of sensuality are “not your proper range.” Sensuality in this context refers to the grasping after sense pleasure. The sense experiences that the mind registers as “agreeable, pleasing, charming, endearing, enticing,” the Buddha indicates, are “linked to sensual desire.” In other words, it’s our tendency to crave these experiences, to chase after them, to want to hold on to them.

The strings that hang from the five sense pleasures represent their “clingable” nature. It’s as if these pleasurable experiences have strings attached to them; and our tendency is to grasp after these strings.

This is an important point. In the Buddha’s teachings, sensuality is not the pleasurable experience; it’s the grasping after the experience. Our problem is found in the way we relate to this experience, in our desire. The Buddha says:

It’s up to the dharma student to examine her relationship to sense pleasure. What is she doing with her mind? Does she let her mind wander off, outside its “proper range?” Does she put herself in a position in which she’s likely to grasp after the strings of sensuality? Does she let her mind become preoccupied with certain sense pleasures? What are the consequences? Is she going into dangerous territory? Is she putting herself at the mercy of the hawk?

Nowadays, of course, the different technological forms provide much of the sense pleasure that we’re apt to indulge in: the television, computer, laptop, smartphone, and so on. The Internet offers a vast array of pleasurable experience, all manner of images, movies, music, words, delivered at a moment’s notice, wherever we are. These technologies provide all kinds of ways to wander outside our “proper range” and into the “territory of others.”

When we wander outside our proper range, “Mara gains an opening.” We suffer. We become caught up in desire and aversion—wanting the various sense pleasures, displeased and dissatisfied when we don’t have what we want. We don’t live in the present moment. And, accordingly, we’re liable to act in unskillful fashion. We find ourselves cut off from the heart.

The dharma student’s proper range is the four establishings of mindfulness: the body, the feeling tone of the body, mind states, and various mental qualities. This is where the dharma student is asked to put her mind. It all begins with the body. First and foremost, in practicing right mindfulness, we learn to keep the mind on the body by putting our focus on the breath.

The body is our proper range. During his 45 years of teaching the dharma, the Buddha was very clear about this. If we can learn to keep the mind on the body, he said, we’ll find freedom from suffering, we’ll be able to know true happiness. In the Dhammapada, the Buddha says:

In offering the parable of the hawk and the quail, the Buddha is making an emphatic point. We should keep our mind in good places; we shouldn’t let it go wherever it would like to go. As the Buddha explains, there’s danger in wandering outside our proper range. The Thai ajahns [teachers] often talk about the danger involved in putting our mind in problematic places. We don’t typically hear Western dharma teachers use strong words like “danger” in describing the consequences of having an untrained mind. But to be certain, there is significant danger in not taking care of the mind, in craving, in grasping after sense pleasure. The danger, of course, is not physical, but mental, emotional, psychological, and spiritual.

If we wander outside our proper range, we’ll suffer. On the other hand, if we remain in our proper range, if we practice right mindfulness, if we keep the mind on the body, we’ll come to know true happiness in this life.

In The Hawk (Sakunagghi Sutta), the Buddha offers a compelling parable to illustrate the importance of practicing right mindfulness. The Buddha didn’t simply teach mindfulness. He taught right mindfulness. In practicing right mindfulness, the dharma student makes an effort to keep her mind on specific objects: the four foundations of mindfulness (or the four establishings of mindfulness, according to Thanissaro Bhikkhu’s translation). If we’re able to do so, we’ll move toward a true happiness in our lives. But if we don’t keep the mind in these places, the Buddha teaches, we’ll be bound to suffer.

The Buddha makes this point by telling the story of a quail who lives in a field with “clumps of dirt all turned up.” As long as she remains in this field, her “proper range,” she’s safe from predators, including the hawk. One day, however, the quail wanders outside the field, and, sure enough, the hawk swoops down and captures her. The quail laments her “bad luck,” remarking that if she’d stayed in the field of turned up dirt, the hawk “would have been no match for me in battle.” The hawk disagrees, and, to make his point, he deposits the quail back in the field. The hawk circles and swoops down. The quail, in turn, conceals herself behind a large clump of earth. And, sure enough, the hawk smashes into the dirt and dies.

The moral of the story is that we shouldn’t wander into what isn’t our “proper range.” The Buddha tells us: “In one who wanders into what is not his proper range and is the territory of others, Mara gains an opening, Mara gains a foothold.” Mara, in Buddhist lore, is the personification of unskillful qualities: desire, aversion, and delusion.

The Buddha goes on to say that the five strings of sensuality are “not your proper range.” Sensuality in this context refers to the grasping after sense pleasure. The sense experiences that the mind registers as “agreeable, pleasing, charming, endearing, enticing,” the Buddha indicates, are “linked to sensual desire.” In other words, it’s our tendency to crave these experiences, to chase after them, to want to hold on to them.

The strings that hang from the five sense pleasures represent their “clingable” nature. It’s as if these pleasurable experiences have strings attached to them; and our tendency is to grasp after these strings.

This is an important point. In the Buddha’s teachings, sensuality is not the pleasurable experience; it’s the grasping after the experience. Our problem is found in the way we relate to this experience, in our desire. The Buddha says:

The passion for his resolves is a man’s sensuality,Our happiness, the Buddha teaches, depends on what we do with our minds.

not the beautiful sensual pleasures

found in the world.

The passion for his resolves is a man’s sensuality.

The beauties remain as they are in the world,

while the wise, in this regard,

subdue their desire.

(AN 6.63)

It’s up to the dharma student to examine her relationship to sense pleasure. What is she doing with her mind? Does she let her mind wander off, outside its “proper range?” Does she put herself in a position in which she’s likely to grasp after the strings of sensuality? Does she let her mind become preoccupied with certain sense pleasures? What are the consequences? Is she going into dangerous territory? Is she putting herself at the mercy of the hawk?

Nowadays, of course, the different technological forms provide much of the sense pleasure that we’re apt to indulge in: the television, computer, laptop, smartphone, and so on. The Internet offers a vast array of pleasurable experience, all manner of images, movies, music, words, delivered at a moment’s notice, wherever we are. These technologies provide all kinds of ways to wander outside our “proper range” and into the “territory of others.”

When we wander outside our proper range, “Mara gains an opening.” We suffer. We become caught up in desire and aversion—wanting the various sense pleasures, displeased and dissatisfied when we don’t have what we want. We don’t live in the present moment. And, accordingly, we’re liable to act in unskillful fashion. We find ourselves cut off from the heart.

The dharma student’s proper range is the four establishings of mindfulness: the body, the feeling tone of the body, mind states, and various mental qualities. This is where the dharma student is asked to put her mind. It all begins with the body. First and foremost, in practicing right mindfulness, we learn to keep the mind on the body by putting our focus on the breath.

The body is our proper range. During his 45 years of teaching the dharma, the Buddha was very clear about this. If we can learn to keep the mind on the body, he said, we’ll find freedom from suffering, we’ll be able to know true happiness. In the Dhammapada, the Buddha says:

They awaken, always wide awake:The dharma student, following the Buddha’s instructions for right mindfulness, makes a wholehearted effort to keep her mind on her body. She doesn’t let her awareness go wherever it pleases. She’s proactive in her efforts to keep her mind on the breath and body. Her efforts are purposeful because she wants to avoid suffering and she wants true happiness. She’s aligned with her purpose—and motivated, as the sutta infers, by a sense of urgency—as she remains mindful of the breath and body. As the Buddha notes, the dharma student, practicing right mindfulness, is “ardent, alert, & mindful.” In maintaining alertness, the dharma student notices when she begins to wander outside of her proper range. She recognizes the movement in her mind suggesting that she should pick up the smartphone to check her emails, for example.The dharma student is ardent and makes a wholehearted effort to keep her mind in her “ancestral territory.” She stays with the body and the other establishings of mindfulness and doesn’t give in to her inclinations to grasp after sense pleasure, to succumb to Mara.

Gotama’s disciples

whose mindfulness, both day & night,

is constantly immersed

in the body.

(Dhp. 299)

In offering the parable of the hawk and the quail, the Buddha is making an emphatic point. We should keep our mind in good places; we shouldn’t let it go wherever it would like to go. As the Buddha explains, there’s danger in wandering outside our proper range. The Thai ajahns [teachers] often talk about the danger involved in putting our mind in problematic places. We don’t typically hear Western dharma teachers use strong words like “danger” in describing the consequences of having an untrained mind. But to be certain, there is significant danger in not taking care of the mind, in craving, in grasping after sense pleasure. The danger, of course, is not physical, but mental, emotional, psychological, and spiritual.

If we wander outside our proper range, we’ll suffer. On the other hand, if we remain in our proper range, if we practice right mindfulness, if we keep the mind on the body, we’ll come to know true happiness in this life.

♦

Peter Doobinin’s previous sutta studies take a look at the Thana Sutta, Yoga Sutta, Nava Sutta, Lokavipatti Sutta, Cunda Sutta, Samadhanga Sutta, Nissaraniya Sutta, and the Gilana Sutta.Via Daily Dharma: Accepting Moments as They Are

Every moment of mindfulness renounces the reflexive, self-protecting response of the mind in favor of clear and balanced understanding. In the light of the wisdom that comes from balanced understanding, attachment to having things be other than what they are falls away.

—Sylvia Boorstein, “The First Teachings”

CLICK HERE TO READ THE FULL ARTICLE

—Sylvia Boorstein, “The First Teachings”

CLICK HERE TO READ THE FULL ARTICLE

Via Words of Wisdom - September 25, 2019 💌

"You and I are in training to be conscious and compassionate in the

truest, deepest sense—not romantically compassionate, but deeply

compassionate. To be able to be an instrument of equanimity, an

instrument of joy, an instrument of presence, an instrument of love, an

instrument of availability, and at the same moment, absolutely quiet."

- Ram Dass -

Tuesday, September 24, 2019

Via Daily Dharma: Open to the Sacred

Despite

our loyalty to our Western materialistic and scientific view, we may

come to suspect that reality is actually multidimensional, that vestiges

of other worlds sometimes accompany us, that a sacred embodied presence

may be available to us if only we are open to it.

—Sandy Boucher, “Meeting the Friend She Always Knew”

CLICK HERE TO READ THE FULL ARTICLE

—Sandy Boucher, “Meeting the Friend She Always Knew”

CLICK HERE TO READ THE FULL ARTICLE

Monday, September 23, 2019

Via Daily Dharma: How to Appreciate Every Season

Ten

thousand flowers in spring, the moon in autumn, a cool breeze in

summer, snow in winter. If your mind isn’t clouded by unnecessary

things, this is the best season of your life.

—Wumen Huikai, “The Best Season”

CLICK HERE TO READ THE FULL ARTICLE

—Wumen Huikai, “The Best Season”

CLICK HERE TO READ THE FULL ARTICLE

Sunday, September 22, 2019

Via Daily Dharma: The Gift of Every Breath

There

was just no telling which breath would be my last. And so I breathed.

And breathed again. And each breath was better than the one before

because it was a gift, an unexpected bonus.

—Leath Tonino, “The Ground Under Our Feet”

CLICK HERE TO READ THE FULL ARTICLE

—Leath Tonino, “The Ground Under Our Feet”

CLICK HERE TO READ THE FULL ARTICLE

Via Words of Wisdom - September 22, 2019 💌

"I always have the same response - I will work on myself since the work

on myself is going to be the highest thing I can do for it all. I

understand that as man up-levels his own consciousness, he sees more

creative solutions to the problems that he’s confronting."

- Ram Dass -

Saturday, September 21, 2019

Via Daily Dharma: How Can You Forget the Self?

One

forgets the self by becoming one with the task at hand. Zazen, or

seated meditation, is the quintessential form for this focused

awareness, but it can be practiced anywhere and anytime.

—Andrew Cooper, “Spirit in Sport”

CLICK HERE TO READ THE FULL ARTICLE

—Andrew Cooper, “Spirit in Sport”

CLICK HERE TO READ THE FULL ARTICLE

Via Be Here Now Network...

In this special episode of the Heart Wisdom Podcast, Jack Kornfield honors the life and wisdom of his early Vipassana teacher, S.N. Goenka.

S.N. Goenka was a pioneer in making Vipassana meditation widely available to a secular audience. Over 170 meditation centers have been established around the globe in his honor. Goenka was an inspiration and teacher to thousands of students from around the world, including Joseph Goldstein, Sharon Salzberg, Ram Dass, Daniel Goleman, and many other western spiritual leaders. Discover the legacy of S.N. Goenka: vridhamma.orgmake the jump here to listen

Via Gayety: Marriage Could Be Good for Your Health – Unless You’re Bisexual

Is marriage good for you?

A large number of studies show that married people enjoy better health than unmarried people, such as lower rates of depression and cardiovascular conditions, as well as longer lives.However, these findings have been developed primarily based on data of heterosexual populations and different-sex marriages. Only more recently have a few studies looked into gay and lesbian populations and same-sex marriages to test if marriage is related to better health in these populations — and the evidence is mixed.

Our study, published online on Sept. 19, evaluates the advantages of marriage across heterosexual, bisexual, and gay or lesbian adults. We discovered that bisexual adults do not experience better health when married.

Friday, September 20, 2019

Via Daily Dharma: Continuous Renewal

Buddhist psychology urges that we recognize that dying is a continuous process, going on all the time—a “perpetual succession of extremely short-lived events.” To recognize this authentically is to experience some form of enlightenment.

—Dean Rolston, “Memento Mori”

CLICK HERE TO READ THE FULL ARTICLE

—Dean Rolston, “Memento Mori”

CLICK HERE TO READ THE FULL ARTICLE

Thursday, September 19, 2019

Via Daily Dharma: The Purpose of Mindfulness

The

purpose of nirvanic moments of mindfulness is to create an ethical

space from which to see, think, speak, act, and work in ways that are

not conditioned by reactivity.

—Stephen Batchelor, “A Buddhist Brexit”

CLICK HERE TO READ THE FULL ARTICLE

—Stephen Batchelor, “A Buddhist Brexit”

CLICK HERE TO READ THE FULL ARTICLE

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)